When I was in the second grade, I ran away from home. I told a classmate at school of my plan, and at the end of the day, when the school bus from P.S. 18 dropped us off a mile east along Hillside Avenue, in front of the Bell Park Manor Terrace garden apartments, I avoided the large center court of apartments where my family lived and followed an alternative route. I wended my way through other adjacent and successive courts, sadly but determinedly following a course in the winter snow up a gently inclining Queens Village residential hill away from home.

I was the youngest of the three children, “the baby,” of a loving but boisterous and volatile, emotionally troubled family. I was painfully sensitive and shy, a dreamy child who played by himself with his toy soldiers and building blocks, read his books and watched his movies on TV from his stomach on the floor, and I shrank before the wild free jazz that was my family’s communication. I tried to join in at the dinner table, but no one, it seemed, would let me play my part, let alone a solo. Then our father, Tablet-shattering Moses of my world, angered by yet another element of this life he couldn’t control, would call a halt to the raucous contention by yelling, “No more talking at the table,” and slam his palm down on it. “That’s all!”

Nothing I said broke though. However loved and pampered I was, I felt disregarded and unheeded. I was no one.

When, in my escape from my oppressors, I reached Manor Road, cutting an arc across the hill, between 229th Street and Hillside Avenue again, I remained in known if not everyday territory. There were more familiar-looking garden apartments and courts to traverse before reaching the next territorial boundary, of Stronghurst Avenue. Ascending hilly walks and steps, I finally arrived there, the outer perimeter of the Manor.

I stopped.

What faced me now were “the woods.” “The woods” – as they seemed to the child I was, a city boy in a gently suburban-like part of an outer borough of New York City – was actually a long corridor of trees bounded by what I could not see and did not know ran along and below the other side of them – the Grand Central Parkway of New York. What they felt to me to be, at seven years old, was the forbidding forest of fairy tale fright such a child as I would never dare to enter.

I was at my limit. I had neither knowledge, wits, nor courage to go any farther. I had not gone far at all. Even more sad and dejected than when I set out, I plopped myself down on my Davey Crockett lunch box to sit.

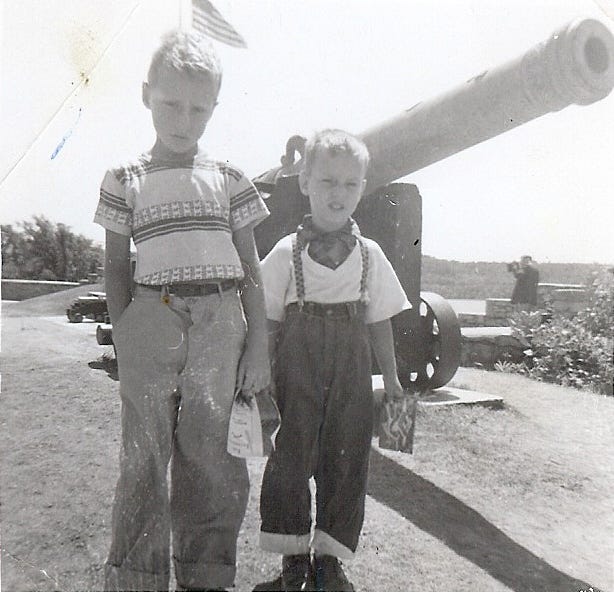

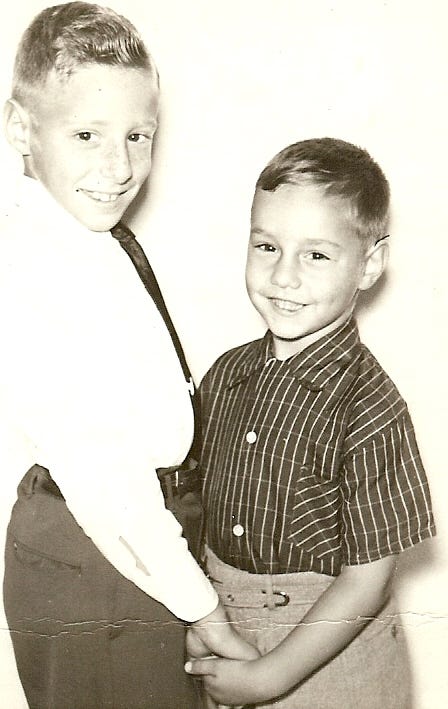

My brother, Jeff, older by five years, a wound coil of anxious energy, known for his innocent mischief throughout the neighborhood as “the little redheaded bastard,” was not no one. Jeff was clearly someone. And as different as we were, ours was a brotherhood of love, hate, and adoration.

With light still in the sky, but the day waning, I spied from my seat on the high Stronghurst Avenue sidewalk, looking back down the hill though the courts, Jeff slowly making his way up in my direction. My school friend, perfidious soul, had divulged my plans, our parents sending Jeff to retrieve me.

I recall his advancing up the hill with all the grudging annoyance of a twelve-year-old boy whose afternoon of adventure had just been spoiled by his pest of a baby brother. Jeff called out to me his sharp warning.

“You’d better not run, you pecker.”

Jeff took me home.

Back in our apartment, it was our older sister, Sharyn, fulfilling the role that only she could, who sat alone with me in the room Jeff and I shared, listening and consoling me as I cried of my pain.

But the role of my brother, if it hadn’t been before, was that day set. For the rest of his life, whenever I was in trouble or in need, Jeff came for me and took or led me home. He rescued me.

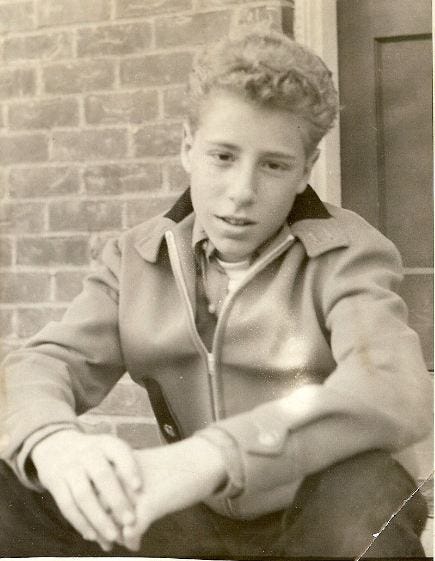

When I was fourteen, and an older boy, amid some football fun, slugged me in the face, it was Jeff, already slighter and shorter than I, who flew at him, taking him to the ground at the knees like a Greco-Roman wrestler, and pummeled him into regret.

If I was lost, Jeff would tell me how to find my way back home. If my first car broke down, old and past repair on a Manhattan street, it was Jeff who came to help me junk it.

When I was seventeen, and the Sixties caught up with me, disassembling my life and psyche in a hallucinogenic descent into hell, it was Jeff, sparing our parents the pain, who was standing beside me in the hospital emergency room, caressing my head as I emerged, broken, back into the world’s dark night.

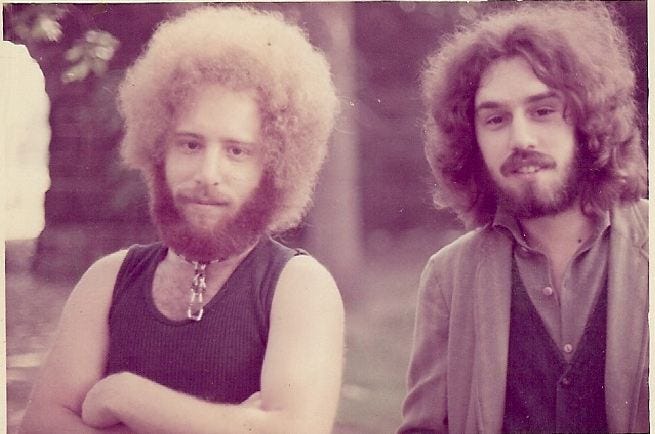

Six years later, running from a love gone terribly wrong, I followed Jeff to Los Angeles, to where he had split to seek his fortune in life. He took me into his Malibu apartment, and I went to work in the antiques business he and some New York friends had opened.

Through all of this time, as I tore within myself against the intensity of my gripping interiority, Jeff was my model of what it was to be free of it. If I wanted to be a more confident and gregarious person, more adept at encountering the world with ease and success, the master of a moment and not a brooder on it, I had Jeff before me to demonstrate how it was done.

I didn’t wish to live the life Jeff was living – we had different passions and were lucky to have them – but in all the ways I was unhappy with myself, I wanted to be Jeff.

Six years later again, my world almost miraculously reconfigured, I was a successful business executive faced with a life-altering decision. Offered a momentous promotion that would mean almost certain wealth, but the loss for sure of the person I knew I was meant to be, I withdrew to my Manhattan apartment for a long weekend of solitude and thought. There should have been nothing to consider. My creative nature and need had inhabited me since earliest childhood. But a brief few years out in the world of an international startup business had saved me from myself, had brought me to myself, or a part of myself I never knew existed. I had encountered life with success and I felt liberated from the lonely prison of myself.

I had become more like Jeff. But not myself.

During that weekend, I spoke to only one person – Jeff, by phone, in Los Angeles. He helped me to make the decision – the opposite of what he would have chosen for himself – but what he understood, talking to me, was right for me.

If our lives were rewards for daring choices in true commitment to ourselves and others, the shape of a pleasing story, in narratives of challenge and overcoming, a decade later mine would not have reached another bottom. But it had. I moved to Los Angeles again, where Jeff – and Sharyn – took me in, gave me places to live while I found work and saved money. Jeff helped me find a car. He helped me find my apartment. Just a few years earlier, when Sharyn had hit her own hard times, she also moved to Los Angeles. Jeff took her in, too, with her daughter. He helped them find a place to live, with good schools. Later, when Sharyn needed a job, Jeff gave her one.

When a speeding car ran a red light into my driver’s-side door, leaving me unconscious and then too fractured to move on my own, it was Jeff who retrieved me from the emergency room, took me home with him with his partner and cared for me until I healed.

When I called him to collect me from another hospital, checking myself out after surgery against doctor’s orders, because “I need to get this fucking thing out of me,” it was Jeff, with our father, who came quickly for me, then sighed to leave me, all my meds and needs arranged on a tray beside me, squirming in pain on the sofa.

It would continue all Jeff’s life, for me, for Sharyn, for our parents. As our mother descended in her last years into the netherworld of Alzheimer’s, (“like being alone in the desert,” she said to me forlornly, staring into space) it was Jeff’s extra burden to be the only voice that could calm her, tamp down the demon of her anxiety.

“I don’t know who you are,” she said to him once from a hospital bed, “but I know I like you.”

Even before, but more yet after she died, Jeff became our father’s best friend. He so loved and admired the small, uneducated immigrant who had shown us such devotion and who faced his great old age and end with fearless calm and stoicism.

* * *

Jeff had left New York for Los Angeles in the mid-Seventies because California, then, beckoned as land of opportunity for young people looking to invent themselves. The nuggets weren’t gold and the strikes didn’t grow into mines, but there were fortunes and futures to be made.

Though his energy was boundless and his personality overflowing, Jeff’s greatest talent, beyond entrepreneurial vigor, was psychological. He had actually majored in psychology in college. He worked his empathetic psychological imagination to make deals, save deals, and bring partners who were falling out back together again, through long nights of listening and persuading people where their true self-interest lay, whatever was pissing them off at the moment. He was a salesman, only he didn’t bullshit you. He learned what your needs were better than you knew them yourself, and he worked to stop you from standing in your own way of them.

So, when other ventures didn’t pan out, real estate sales became his career.

And, of course, using his knowledge, when the timing was right, he got me and Julia into a house we otherwise couldn’t afford to buy.

As he developed into a different person over time, with different needs himself – a little bit more like me – Jeff thought to change careers, earning a master’s degree in psychology. But around the same time, in the mid-2000s, he and some partners made a move into ownership, purchasing some residential buildings. This, he thought, would enable his move to another level.

They didn’t see 2008 coming.

Sometime around Passover in 2011, Jeff and I met for a dinner at Nate ‘n Al’s Deli in Beverly Hills. We tried to feel our mother’s love in the stuffed cabbage, recall our father’s joy in a pastrami sandwich. We talked about our lives. We talked about the difficulty I was having selling the 37-foot motor home I’d bought with home equity and that had carried me and Julia through our sabbatical year on the road. The only buyer I could find was the same dealer we’d purchased from, getting his own back now from the great deal I’d been able to negotiate in the crashing economy of ‘08. With the dealer offering only two thirds what I knew the motor home was worth in a good economy, I was bucking at making the deal.

After thirty years of selling real estate, Jeff was now facing this complaint every day, trying to persuade unhappy homeowners pressed to sell that the only thing worse than selling their homes now for prices they didn’t like was selling them six months later for prices they would like even less. You need the money, he said. When you have the cash in hand and you’re relieving all those financial pressures, you’ll feel good about it and focus less on the price you took for the sale.

I listened. We finished dinner, took a stroll, and stopped in at the bar of the Mirage Hotel. We sat in a couple of club chairs and enjoyed our scotches. Now Jeff talked. While I had been living my great adventure on the road for a year, his financial life had fallen apart. That I knew already. By 2011, the residential properties were gone. Jeff was deep in debt and double mortgaged on his home. Though he had taken up tennis with enthusiasm in his mid-fifties, he’d also gained a lot of weight over the years. He showed stress I’d never seen in him before. For two years he could barely sleep at night. Everywhere he tried to make some light, it got only darker. He was afraid he would lose everything. Now, he was cutting back on his health insurance coverage. Anne had chronic ailments, so he was maintaining the coverage on her, but he was saving a few thousand dollars by reducing his coverage to what was, practically, a catastrophic plan. We considered the risks.

“The bottom line,” he said to me, “is you never know what’s going on inside your body.”

Finally, we walked to the same underground parking lot in which we’d both coincidentally parked. We descended the elevator, first to the second level for him, then on to the third for me. When the door opened, we hugged and kissed on the check as we always did, and he walked out into the garage toward his car. I followed him with my eyes, I see him still, as the door closed like a shot in a film, and he was gone.

About three weeks later, he called on a Sunday morning. For the first time since we saw each other, things were looking up. He had closed a bunch of deals – he had been working so hard, never giving up, driving himself – and money was coming in. In July, Sharyn, now living in Cleveland near her daughter and grandchildren, would be celebrating her 70th birthday. Her son, Rob, cousins, and I were flying out for it, but Jeff had long said he couldn’t afford it and couldn’t afford to get away. Now he said he could. He had looked into booking a flight, might fly with me. He also wanted to go on to New York with me afterwards, where I had planned a long visit. He would stay with me for a week or so.

We were so excited. We hadn’t been to New York together in over a decade. Now we would walk the streets again that ran in us like the blood in our veins. We would breathe it all in, remember our youths and our family in it.

Then I told Jeff that since our evening out, I’d sold the motor home. I basically accepted the dealer’s price, squeezing another thousand dollars out of him. Jeff was so happy to hear it, even happier when something I said just before we hung up made clear that it was our talk over dinner that persuaded me. He had been right. Cash in hand already, problems getting solved, I was feeling okay about it.

“Really?” Jeff said.

He paused.

“I’m really glad you told me that.”

Then we hung up, planning to speak in days about our flights to Cleveland and New York.

* * *

Julia’s and my dinner just ended, my cell phone had rung now five times, an unknown caller leaving no messages. Those dinner time sales calls could really interrupt a good Cabernet buzz. And then the sixth time, the sound of a voicemail. I listened. It was Anne, his partner. Could I call her on Jeff’s cell phone, she asked in an even voice.

I had barely ended the call and begun to form the thought when Sharyn’s number showed up on the screen.

I’d already risen and begun to walk for some reason toward my desk, off the kitchen.

“Sharyn?”

“Have you spoken to Anne?”

“I just listened to a voice mail asking me to call.”

I had reached the desk.

“Are you sitting down?” Sharyn asked.

I had sat down.

“What?” I said urgently. “What?”

“Jeffrey’s dead.”

My head dropped toward the desk like a bomb, the howl of protest rising up against it along with my fist, clenched with the fear that I’d buried, but not deep enough.

No! No! No!

My fist pounded the desk with each growling, aching cry of agony.

No! No! No! Fist pounding, up, down in great strikes with every scream.

Julia ran to me, in tears, threw her arms around me from behind.

“What is it? What’s wrong?”

We sobbed, we shook, we lamented. Jeffrey, Jeffrey, dear Jeffrey.

Quickly, we had to gather ourselves.

I’d told Sharyn we would go to the emergency room. Anne was still there waiting with Jeff’s oldest friend. I stood at the door before we left, as Julia collected some last items, my body wracked and shuddering inside the way it had the night in Paris I nearly choked to death and Julia saved my life.

I thought I would have a heart attack myself.

Julia drove. I called my department chair from the car, asked her to cancel my classes for the next day. I turned to the window.

From Marina del Rey to West Hills in the San Fernando Valley, thirty to forty minutes at that time of night, to think, to sit stunned in the well of the passenger seat and watch the black, bleak profile of the Santa Monica Mountains pass on either side, constant witness to the long procession of the dead and grieving.

We turned into a parking lot we had visited many times. All the illnesses of my parents’ declining years, taking my mother home to die in her bed, standing around his hospital bed to watch my father die.

Now, just a few years later, Jeff.

* * *

In the years since that night, I have thought so often about who my brother was to me, what he was in my life, and how to live my life without him. By now, I’ve lived it without him for nearly 14 years. I had imagined, with the kind of hope to which we all cling, that he and I would become old men gabbing together. We talked about it.

I had thought that as time took so much of its payment for long life, if one is lucky enough to have the barter, the same reflective shadow that had hovered over me since my earliest memories, in that childhood bedroom, would still be with me to remind me, against all the growing sense of the illusory passage that advancing age brings to life, that it had all been real and just as I remember, because he had lived it too. That I would be the same for him.

I have no memory of life before that bedroom, no recollection of experience before experience with Jeff.

I have thought about who we were as personalities, as people with qualities and attributes, skills and talents. It began to seem true to me that for all the stark differences visible in childhood, and that had diminished with age, we had actually lived as variations on a theme. I began to think of us, in an odd conceit, in terms of a graphic equalizer for audio. Each graphic band for a frequency might represent sociability or introspection, athleticism or intellectuality, shrewdness or nurturing care, sense of humor and world view. All of the same frequency channels were present in both of us. Adjust this one higher, this one lower, these two now up over here, down just a little bit there, all of these, so many, the same, and in one case you got Jeff, the other me.

It isn’t as if we were identical twins. We lived different lives, for several periods in different cities and states. Our brotherly relationship was not without blemish. I know there were times that I disappointed him, even hurt him, even deeply. And with death, regret is a rock you push up a hill for the rest of your life.

But if, in the spirit of the Mishnaic dictum, each of us represents a whole world, storing webs of association and memory in sensory connection and personal relation, with apprehensions of human history and of the universe, and emblazoned on the film of our minds the vision of a certain quality of light on the farther streets and lawns of New York City in 1957, and, with all of it, an intuition of the further worlds that lived in some other people at other times and places over the course of our coming and going, then there was no world closer to mine than Jeff’s. Unbeknownst to me to start, increasingly by the end, he was my secret sharer of experience, by which a self is reflected to itself in the presence of another. In the first weeks and months after he left us, there were conversations that began in me, directed to an internalized, anticipated Jeff, which were then cut short in surprise – conversations for which there is no substitute for Jeff. Parts of me are now dormant, never to awaken again. The loss of a person you love is the loss, too, of a part of yourself.

* * *

A few days after Jeff died, I eulogized him at his memorial service. I tried amid my grief to capture the very great fun of Jeff, and there was much laughter. I described how, in that early shared bedroom long ago, I, the perfectly credulous, sucker younger brother, had helped his older sibling perfect the tortures of his teasing. How Jeff, demonstrating for me the method of forming globules of saliva at the tip of the lips, taught me to share goodnight “bubble kisses” with him. How, when he studied modern dance in college, I served as sole audience for his choreographed solo. I struck some of his poses that day, in a loving mockery I knew would give him joy, and did the assembled.

The rest of the family spoke, and we invited friends and coworkers to share their memories and feelings too. It was a minor revelation to meet so many people his family did not know who appreciated Jeff so much and for the same qualities. No one failed to speak of Jeff’s bonhomie and his outrageous sense of humor, including the loud, cackling laugh that could dominate a room.

Among the last to speak were Jeff’s tennis buddies, the men who had been with him at the end. They shared with me privately what had happened on that last evening, on the tennis court with his friends, Jeff beginning to feel funny. A minute or two later, having retreated to the bench, where his pals hovered over him, his head jerked back from the rupture in his chest, and he fell to the floor. His friends then tried to do with all that was in them what I have wished every day since I could do – rescue him.

To a man, they spoke not only of Jeff’s caliber as a player, but also of what a great teammate he was, always encouraging his fellows, even on his own off days. When the last of them spoke, the reminiscence took a surprising turn. This friend reiterated how fine a teammate Jeff was. Then he said something else. The friend is Black, and when he said it, he spoke the word “wasn’t” with a Black vernacular pronunciation, in which the “s” is elided, that aided the delivery. And his timing, with the briefest delay, was perfect.

Sure, Jeff was a great teammate, he said. But as for his play – and here he shrugged and squinted a slight shake of the head.

“He wuhdn’t that good.”

You could sense – I thought I did, anyway – a hiccup in the room, as if some felt – momentarily, perhaps – that something inappropriate had been said. But those who knew Jeff best, and then the rest, roared with sudden laughter. His friend well timed a repetition of the line as he turned away, and we all roared again. Nobody loved more than Jeff, after his father, to puncture pomposity or a too solemn moment.

A week later, our nephew Rob and I were speaking on the phone, recalling the moment and the joke, and how Jeff would have loved it. The memory of it is part of the memory of him now and of his end, and that is just as he would have it.

Except that he was that good. He was.

AJA

This essay first appeared at A. Jay Adler’s Substack Homo Vitruvius.

Brimful of love and insight, this is one of the most affecting family memoirs I’ve read on Substack. It has stayed with me since I found it last year. What a pleasure to read it again.

What a beautiful tribute, A.J. I have four older sisters. I’m 66. We’re all getting together in May for our middle sister’s 70th birthday. Your story reminds me to pay attention and be grateful. We know not the hour nor the day.