I admit it: I’m a story-topper.

Not because I need the last word—but because stories are how I remember. They’re how I hold on.

When someone fires off a good one, something in me leans forward. Fingers twitching. Brain already halfway to the next chapter.

I come by it honest.

The Glover family tree is tangled with storytellers. But the root system? That’s all Benjamin Franklin Glover—my grandfather. Grandad Ben.

Born on Leap Day, 1908. Raised in the rugged Boston Mountains of northwest Arkansas, in a world without electricity, without plumbing, without backup plans.

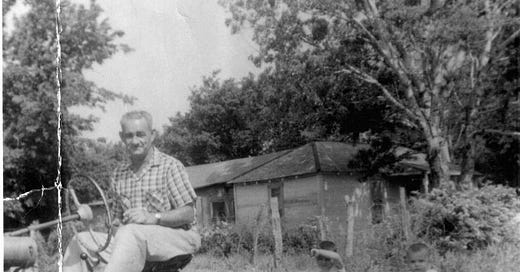

He came up with calloused hands and a back like an oak beam. He could drive a team of draft horses, swing a twenty-pound sledge like a broomstick, and forge steel in a fire he built himself. His backyard shed was blacksmith’s kiln, wood shop, repair bay, and magic cave all rolled into one.

We watched him like disciples.

One leg powered the grinding wheel. The other braced it. The sparks didn’t just fly—they sang.

When that axe came down, it didn’t split wood. It cracked the earth.

He smoked Prince Albert tobacco from a red tin with a flip-top lid. Could open the can, pour the tobacco, roll the cigarette, and strike a match all in one fluid motion. One hand did the rolling. The other struck a kitchen match on his thumbnail like he had flint in his blood.

He smoked those roll-your-owns for decades—until the heart doctor gave him a choice. So he laid them down. No bargaining. No patches. No complaints. Just one more iron-willed decision, made with the same force he used to split logs.

That was Grandad. Quiet. Steady. Always working.

He raised rabbits and hogs. Butchered chickens. Sharpened every blade in the county. And when we were little, he’d pop out his false teeth and chase us around the porch like a madman—scaring us half to death and making us laugh just as hard.

But the best part? When the work was done, he told stories.

Not just “a guy walks into a bar” stories. These were full-cast productions. Voices. Pauses. Body language. Sound effects.

You haven’t lived until you’ve seen a grown man imitate a possum fight using just his hands and throat.

But the story that froze our spines—and lit our imaginations on fire?

The bobcat squall.

It started low, curled up your backbone, and came screaming out like a wildcat trapped in a rain barrel. Shrill. Sharp. Close enough to rattle your bones.

We’d be mid-story—me and Dennis crouched on the porch like coiled springs—when Grandad would let it rip.

That sound hit your nervous system before it reached your ears. Like lightning striking bone.

Dogs barked. Knees buckled. Dennis hit the dirt.

I’ve tried to mimic it countless times. Can’t do it—not even close. But even my sad imitation still gets a reaction.

Because his wasn’t just a sound. It was a summons. A signature. A spell.

And then one summer—we heard the real thing.

We were at Uncle John’s cabin near Mountainburg, deep in Grandad’s old woods. I was chasing Dennis around the yard (barefoot, half-serious) when it came.

The real squall. From the trees. Wild. Primal. Unfiltered.

Dennis stopped dead. I did too. For a heartbeat, we stood frozen.

Then we ran—like we owed that thing money. First and only time I ever outran Dennis.

That’s what Grandad’s stories did: they trained our ears for wonder, even when the real world came calling.

But time snuck up.

Not with a bang—but with a leak.

A forgotten name. A broken sentence. A long pause where the next line used to be.

We didn’t call it anything back then. Just said he was getting older.

But it had a name: Alzheimer’s.

It came slow. It came cruel. First the stories. Then the rhythm. Then the voice.

Piece by piece, the magic slipped away. The sparks dimmed. The wheel slowed.

But we still listened.

I never got the bobcat squall recorded. Never got the stories written down.

And that’s why I’m writing this now.

Because if Grandad could conjure a bobcat on a porch in Picher, maybe I can keep him alive—on paper, in print, with the same rhythm and love he gave us for free.

He was the original storyteller. The man who turned memory into music, sound into spell, silence into laughter.

And I’ll be damned if I let those stories disappear without a fight.

That squall is in my blood too—crooked and loud and impossible to ignore.

And that trip to Uncle John’s?

It wasn’t even the wildest thing that happened that week.

Let’s just say: Dennis never saw it coming.

Not all the danger came from bees or bobcats.

Sometimes, it dropped from the sky—loud, fast, and without warning.

📖 If you believe stories like these matter—if you want to help preserve the memory of small towns, big-hearted families, and porchside roars that echo for generations—please subscribe and share.

Every reader. Every share. Every word passed down—it all helps.

Let’s keep the stories alive.

Thanks for sharing your Grandad with us; his gift of storytelling verbally is yours written. Hope you continue to keep it alive.

I have a hankering for the book… probably multiple copies!