I’ll Never Forget My Father’s Last Breath

It left his body the same way he lived — a fight to the end

I couldn’t believe I was in that room again. The same room Mum died in ten years earlier. My father lay in the bed now. Was it the same bed? Surely this was some twisted prank the gods were playing. In what universe do two parents die in the same position, a decade apart? This one, apparently.

A morbid thought clouded my judgment, and a wave of guilt settled over me like an old, comfy cardigan.

Talk about payback, Dad, I guess you do reap what you sow after all.

I wasn’t being cruel, just stating a fact.

My father hated hospitals. Until that year, as far as I know, he’d only ever been once in his life when he had a massive heart attack in 1997. He’d been at the beach with Mum that day, collecting cunjie in twenty-kilo buckets to use as fish bait. Dad was a keen fisherman.

They weren’t far from their home away from home on the south coast of New South Wales, but they were ten kilometres from civilisation when Dad started feeling chest pain. By the time they reached the car at the top of a hilly cliff face, Dad was 80% of the way to a full-blown cardiac arrest.

He placed the two buckets he was carrying in the back of the car and drove to a medical centre. Mum couldn’t drive; she never got her licence. She was terrified of moving traffic, along with the million other things she was scared of, including Dad in earlier years.

Without a mobile phone—though it likely wouldn’t have worked in such a remote area—Dad understood there was no other option if he wanted to survive. And Dad wanted to live to the age of one hundred. Why, I don’t know. He was as sure of his mortality as he was of his own strength.

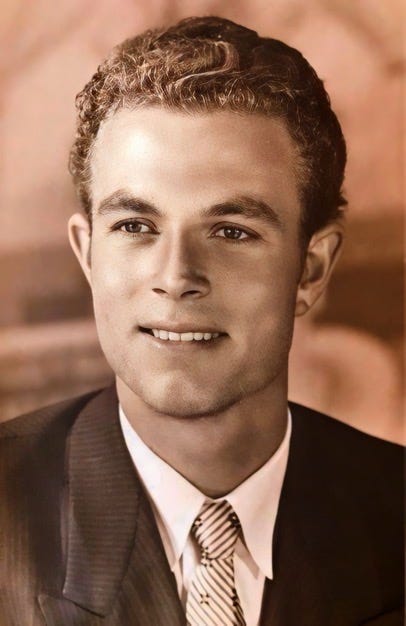

My father had the soul of a gladiator, the heart of an emperor, and the mind of an unpredictable warlord. He was a force of nature—a giant of a man who ruled his kingdom with fists of steel.

You’d better look the fuck out if he was having a bad day; you didn’t want to get in his way if you were smart. And if you were his target, which my brothers usually were, pray to all the gods for your survival. At least have an ice pack on hand; you’ll definitely need it.

My brothers needed more than that, and so did Mum at times. I was lucky, a silent witness to the carnage. I knew how to keep my mouth shut better than my mother or brothers. Plus, I was good at hiding. Out of sight… and all that.

Dad was something of an enigma to the outside world, a legend within the medical profession. What man drives himself to the hospital in full-blown cardiac arrest and lives to tell the tale? Hulk, that’s who.

The beginning of the end can be elusive

In March 2016, Dad fell in the driveway while reaching to pull a weed from his Babylonian Garden. My father was a master gardener; he could’ve been a horticulturist in another life. He could graft two fruit trees together and create a whole new hybrid fruit, plant, or flower as if by some kind of magic sorcery.

I assumed it was a skill he had learned from his father or grandfather, perhaps, while growing up in a village in northern Italy during the 1930s and 40s. But Dad rarely talked about his childhood or shared much about his upbringing. Over the years, I heard brief, fleeting stories from Mum.

Dad was a ten-year-old boy when Germany occupied Italy in 1943. Nazi soldiers moved into his family home. His father was sent off to a POW camp, while his mother and aunts became their maids. They became other things as well, forced into unspeakable acts—a life made of nightmares.

As the eldest son of four siblings, it was up to him to become the man and do the chores his father couldn’t do. He left school and never returned. The skills he’d need aren’t learned in front of a chalkboard.

He saw an aunt’s dismembered body after a bomb explosion near his village. I’m not sure how you ever unsee that. The war ended, and his father returned by some miracle. At seventeen, not speaking a word of English, he boarded a ship to Australia. He never went back to Italy or saw his family again.

My father drank every day; whisky and red wine were his staples. I don’t ever recall seeing him drunk, which seems ludicrous to me now. How is that possible with the amount of alcohol he consumed? It is simply blood to Italians, I suppose.

I have one memory, though, that could only be explained by intoxication. It is seared into my mind so perfectly that, even now, I can see every detail. It was a family gathering—Mum’s extended family, Christmas perhaps—more people in our house than I’d ever seen before. A sound so beautiful suddenly pierced the air, causing all movement and noise to stop. My father stood like a beacon, right there in the middle of the kitchen, singing Mario Lanza’s ‘Mamma’, solo, no music.

How did the voice of a tenor come from my father? And as a tear fell from the corner of his closed eyes, my disbelief and shock held me rooted to the spot. Everyone was mesmerized. My father—he of little faith or words—was singing to a crowd and crying.

What. The. Fuck.

The applause was deafening. Who was this man? I didn’t have to wonder long. I never saw him again.

Back in the driveway

Dad broke his femur in the fall. Trust Dad to break the biggest bone in his body; he never did things by halves. He lay on the concrete for two and a half hours before the postman found him and called an ambulance.

Then Dad called me. I flew from Perth, where I was living at the time, to help him get back on his feet. Six weeks later, I reluctantly left him in the hands of my brother Greg.

Greg was dutiful in those later years. He’d promised Mum on her deathbed that he would, indeed, do his best with Dad. I don’t know how my brother forgave him, or if he even did, for a childhood filled with violence and emotional torture. He remained an enigma to me.

I’d spent those six weeks going back and forth from the hospital while also making Dad’s house more accessible and convenient. I cleaned that house to resemble a well-oiled machine; I could’ve Instagrammed the shit out of it. I doubt it had seen a spring clean since Mum died. I filled his fridge and cupboards with every item imaginable, so he wouldn’t need to shop for months.

Dad was the king of frugality, and most of the things he ate came from his garden. Greg would have to manage that for a while, not that he was as flexible as Dad (before the fall) or had the same green thumb. Greg had more health issues than our eighty-three-year-old father. I guess he took after Mum in that respect, and a lifelong heroin addiction didn’t help his situation.

My phone rang a few days after I got home, and Dad shouted from the other end.

“Where’s my thingy? Why did you clean up? I can’t fucking find anything now. Stupid!”

Nice. A simple 'thank you' for all your hard work would have sufficed. I cried for a few days. Greg called.

“Don’t worry, sis, he’s just pissed about having to slow down. He can’t do the same things now; that’s gotta hurt. He likes things the way he likes them. You know Dad.”

Yes, I did. And while he’d mellowed a lot with age, glimpses of a distant past were still visible in the cracks.

I called him every Sunday without fail. Each call felt like Groundhog Day as I fished for conversation with him. We talked about the weather, the tides, the garden, and which knucklehead had annoyed him, usually a politician. He never mentioned the phone call that made me cry or spoke of the house again, nor did I.

That fall, though, was the catalyst for my father’s breakdown. He slowed down, alright, spending less time in the garden and more time eating processed food—something he’d once loathed and refused. He also drank more, but that hardly mattered; my stealthy father could handle it. But the body can only take so much when it goes from pristine to rubbish.

His stroke occurred late in November that year, and this time, it would be his final hospital visit. He’d collapsed on the kitchen floor but managed to reach the phone to call an ambulance. Thankfully, he never locked the doors. That’s where they found him, half-paralysed and in a state of catatonia. They were astonished that he could have made the call.

They didn’t know my father. Clearly.

Greg and I took turns at his bedside, and Dad made progress at first. He could talk well enough for us to understand, but the nurses couldn’t hear past his strong accent, which he never lost. He’d been in Australia since 1957, yet at times it was like he had just got off the boat. Dad rarely needed words to communicate anyway. No one knew that better than we did.

He asked for whisky. Greg and I smirked at each other. Can you believe this bloke, seriously? We gave him the whisky, disguised as water in a paper cup. The nurses were none the wiser. Greg proclaimed, "What did it matter at this point? He’s dying anyway." I had no objections. He was right, for once.

Dad deteriorated fast, and he stopped asking for whisky – or anything at all. Greg had gone home for a break, leaving me alone with him, unaware that this would be his last moment.

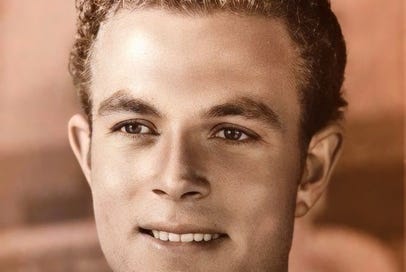

I gently sponged his dry mouth, cleaned his teeth, and combed his hair. I talked the whole time about silly, frivolous things just so he knew I was there. I probably said more to him then than at any other time in my life. I’m not sure where my words came from; I’m not usually chatty in moments of despair.

As I stood ‘fussing’ over him, he opened his eyes and looked deep into mine. It was a moment of absolute stillness. I wondered what he was thinking. Did he know this was his deathbed? Did he have confessions he could finally speak? Was it love I saw in his eyes?

“You alright Dad?” I smiled and touched his face reassuringly. I saw in him something innocent, something I’d never seen before. I thought of his childhood, not my own, and felt a pain so deep I swear it was a glimpse of his soul. Silent tears fell down my cheeks as I held my smile for comfort.

“It’s ok Dad, don’t be scared. You can go now if you want.” The words slipped from my mouth as a whisper. Those were the last words I said to my father.

He closed his eyes tightly, not gently, not serenely, not to drift off into a peaceful slumber. He squeezed them as if a million suns were shining on his face. His mouth opened to reveal gritted teeth so harsh that I could see the white of his gums. Had an unbearable pain seized him? This was nothing like my mother’s last moment, not one bit.

I held his hand in both of mine with the slightest touch of pressure. As he expelled his last torturous breath, a sound escaped me like a wounded animal. And then he was gone.

I collapsed onto his body and sobbed into the bed quilt. Who knew I’d have so many tears for a father I’d hardly known? I cried for all the words he couldn’t say, for the trauma of a childhood he couldn’t face, and for all the sorrys he owed. I will carry them with me now, for him, my reluctant father.

Thanks for reading, friends. If you’ve had the privilege of witnessing a parent's last breath, I hope they found peace in their final moment.

A version of this story was published on Medium.

© Marcia Abboud 2025 | All rights reserved

Some Kind of Life is my personal Substack publication. To receive new posts and support my work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

And because it all adds up, here are my discount rates. Thank you for your generosity.

$1 per month – every dollar counts

$2 per month – double trouble

$3 per month – middle ground

$4 per month – the high road

$5 per month – full price - you’re a legend

No cash? No problem!

Clicking the ❤ button makes my day. Thank you for being here. xx

This was heartbreaking and beautiful. Thanks for sharing.

How poignant and sad on so many levels, Marcia. I am in amazement and wonder that you were able to overcome any bitterness or hate towards him, like so many other daughters may have. You are one strong, compassionate and kind person. So glad I met you here on Substack. :)